May Day: Workers’ Struggle in New York

Greetings to all laborers this international workers' day!

One hundred years ago today … It was May Day, meaning it was Labor Day all over the world, but not in the US.

Labor Day is usually celebrated on the first Monday of September in the US, but in solidarity with the diverse workers in New York and workers across the globe, NY 1920 is dedicating this day to the social and economic achievements of workers who are the backbone of the community. Both days celebrate the fruits of the union movement, such as five-day/40-hour/week, overtime pay, sick leave, workplace safety procedures, health insurance, and paid vacations. We will dedicate a separate piece for the usual American Labor day.

Brief History of Labor Day

The US Labor Day actually has NYC roots. A labor activist and machinist named Matthew Maguire founded this holiday in NYC. He served as the secretary of Local 344 of the International Association of Machinists in Paterson, New Jersey, and later proposed the labor day holiday in 1882 while he was serving as the secretary of the Central Labor Union in New York. Emphasis to Labor day was given through the years by the nation through municipal ordinances passed during 1885 and 1886, and from these developed the securing of the state legislation. The first state bill was introduced into the New York legislature.

Figure 5-3, The Evening World, May 1, 1920.

As outlined in the first proposal of the holiday, the observance and celebration of Labor day is in the form of a parade to exhibit to the public "the strength and esprit de corps of the trade and labor organizations" of the community. This is followed by a festival for the workers and their families' recreation and amusement, and speeches by prominent men and women emphasizing the economic and civic significance of the holiday.

How was Labor Day celebrated 100 years ago today in New York?

May 1, 1920 in NYC, not coincidentally the Socialist Labor Day, was a day designated for a major Boys' Week public parade. Boys' groups that participated in the event come from all sorts of backgrounds, but did not have an organizational affiliation. Governor Alfred E. Smith even wrote on March 23, 1920 while endorsing the idea, that the event was an "insurance policy against Bolshevism and Radicalism."

New York City's Boys' Week was so successful that the idea spread across municipalities and became a national phenomenon. Ironically, May 1 became Loyalty Day in 1921 and became a holiday for Boys' week and "citizenship training." According to a New York Times report in 1925, "most accounts concern themselves with the Rotary Club and the politics surrounding the need to enforce a sense of American loyalty in its boys."

Take a glimpse at how Boys’ Week looks like in this picture from a Massachusetts parade:

Boys' Week p.15, The Rotarian, July 1925.

May Day & Radicalism

The suppression of radicalism is inextricable from US history, and New York is not exempt from it, as seen from this May 1 incident. However, this does not stop unions and radical organizations (which includes anarchist, socialist, and communist parties) from keeping the International May Day tradition alive through rallies and demonstrations. May Day parades, especially during the Great Depression of the 1930s took place at NYC's Union Square. Some large demonstrations have been greeted with violence, even peaceful parades, such as that of the 1919 incident.

Immigrant Laborers

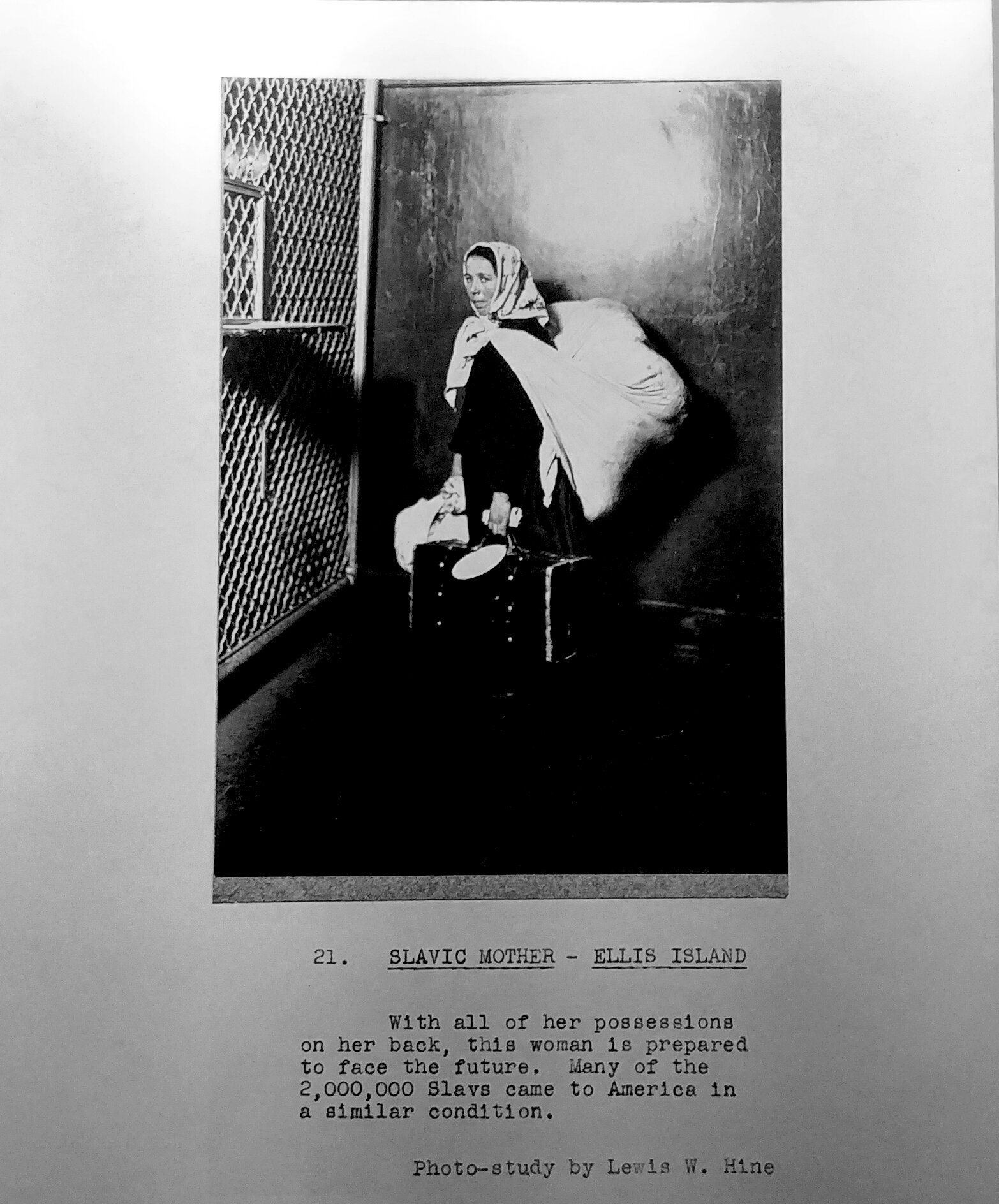

Immigrant workers of NYC play a huge role in its economy, and have helped build the city. Lewis Hine, one of NYC's most notable and influential documentary photographers (previously featured in our January 4 and March 16 posts), examined the life of immigrant workers in NYC. Take a look at this gallery of some of his photographs from his collection "Unit I, Immigration":

Unit I, Immigration - 2. Italian Family En Route to Ellis Island. Lewis Hine. 1920.

Unit I, Immigration - 69. Wife of a Slavic Miner. Lewis Hine. 1920.

Unit I, Immigration - 21. Slavic Mother - Ellis Island. Lewis Hine. 1920.

Unit I, Immigration - 52. French Worker Making High-Grade Tapestries - New York City. Lewis Hine. 1920.

Unit I, Immigration - 55. Jewish Garment Worker - New York City. Lewis Hine. 1920.

Unit I, Immigration - 100. School Nurse - New York City. Lewis Hine. 1920.

New York City, the cultural, financial, and media capital of the world— would not be possible without the people that work everyday to keep the city alive. Let us not only remember the laborers behind NYC, but also strive to hear their call.