New York Dada—or Dadaglobal?

Today’s guest-post is by MARIANA AGUIRRE, Instituto De Investigaciones Estéticas (UNAM), Mexico City. (Bio below.)

One hundred years ago today … The April 1921 issue of New York Dada, edited by Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray, brought the Dadaist movement to New York readers. There were no further issues.

Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray, Cover for New York Dada, April 1921. Monoskop.

Duchamp and Man Ray, Belle Haleine, Eau de violette, 1921. Detail from cover of New York Dada. Monoskop.

Most histories of Dada note that it arose in Zürich around 1915 as a reaction against World War I and later spread to other European cities, most notably Berlin, Cologne, Hannover, and Paris. A similar nihilistic and anti-aesthetic impulse arose in New York in 1913, largely fueled by the migration of figures such as Francis Picabia and Marcel Duchamp and by the support of Alfred Stieglitz and Louise and Walter Arensberg. The publication New York Dada, edited by Duchamp and Man Ray in 1921, recognized the rise of this movement beyond Europe and cemented the importance of “little magazines” for its development. Duchamp had been aware of Dada since the war, and Tristan Tzara, one of its early promoters in Zürich and Paris, collaborated with his magazine. Other than codifying a novel strand of Dada, New York Dada appropriated the format and contents associated with magazines aimed at women, abolishing the barrier between high art and mass culture.

Like other proto-Dada and Dada magazines, such as Stieglitz’ 291 (New York, 1915-1916), Tzara’s Dada (Zürich and Paris, 1917-1921), and André Breton’s Littérature (Paris, 1919-1924), New York Dada’s contents were fragmentary and did not advance a clear program. Its cover featured a fake perfume bottle, Belle Haleine, Eau de voilette (Beautiful Breath, Violet Water), which was decorated by a photograph taken by Man Ray of Rrose Sélavy, Duchamp’s female alter ego. This photographic gesture was tied to Duchamp's readymades, since he modified a bottle of Rigaud perfume by creating a ‘new’ label to advertise the eau de violette. The magazine's cover also featured the words 'new york dada april 1921' upside down, which were repeated in order to create a pattern, subverting mass publications' reliance on typography and mastheads to attract readers. Although the modified perfume bottle has overshadowed the rest of the magazine’s contents, its inclusion announced the importance of commodities and the blurring of gender norms within New York Dada. Additionally, Man Ray’s documentation of Duchamp’s cross-dressing recalls the antics of other figures which were part of New York Dada, especially Arthur Cravan and Elsa Hildegard Baroness von Freytag-Loringhoven, although the latter were more confrontational and performative.

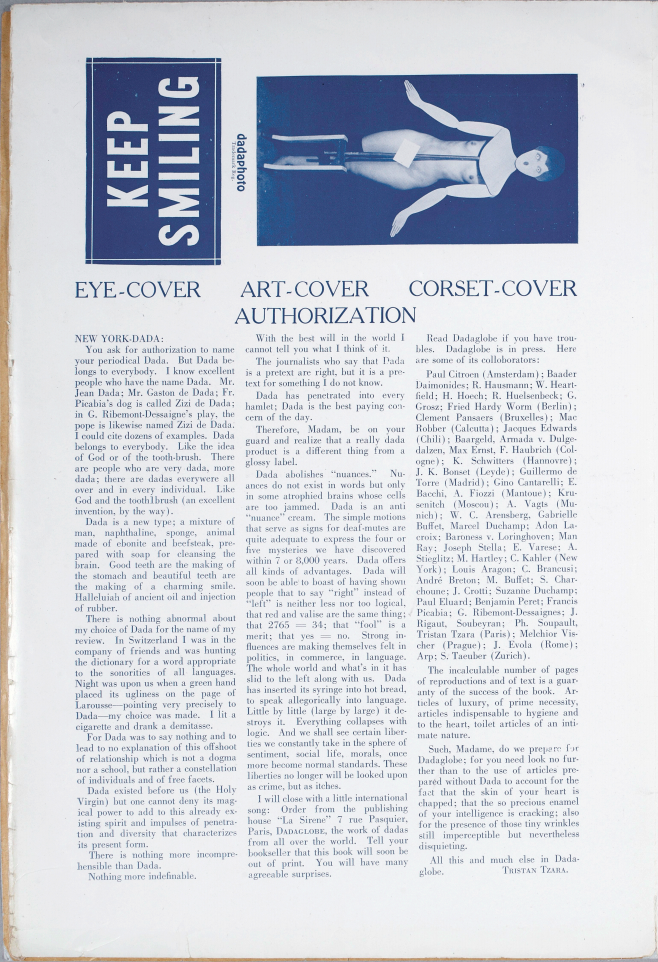

Art historian Emily Hage has described New York Dada as a readymade that parodied magazines aimed at women as well as serious modernist magazines and their manifestos. The first page includes a photograph by Stieglitz of a woman's leg clad in a high-heeled shoe, and together with its accompanying text, recalls magazine advertisements. It is followed by a letter by Tzara, which responded to the writer and art critic Gabrielle Buffet’s request to use the name Dada as part of the magazine's title. The letter takes up most of the page, and is illustrated by Man Ray’s female nude, The Coat-Stand (Porte manteau, 1920), and by a sign that says “KEEP SMILING.” The next page features a cartoon by Rube Goldberg, an underground illustrator who created pornographic comic books known as Tijuana Bibles. It also includes a short, nonsensical text on ventilation and an announcement of a debutante ball that was to be offered by the poet Mina Loy in honor of two other artists affiliated with New York Dada, Marsden Hartley and Joseph Stella. The last page contains two topless pictures of the Baroness and an anonymous poem that several scholars have attributed to her. The only advertisement included in the magazine was for an exhibit of Kurt Schwitters’ collages at Duchamp and Katherine Dreier's Societé Anonyme, an organization which promoted modernism in the United States. In line with the magazine's approach to gender, the ad includes a pun that seems to refer to the artist as female: "DON'T MISS Kurt Schwitters and other ANONYMPHS at the SOCIETÉ ANONYME" (emphasis mine).

Editor’s note: Aguirre contributed a NY1920s guest-post about the Societé Anonyme for May 5, 1920.

New York Dada, page 4 with photographs of Elsa Hildegard Baroness von Freytag-Loringhoven and a poem attributed to her, “YOURS WITH DEVOTION trumpets and drums.” Monoskop.

Tzara's letter also contributed to New York Dada's imitation of magazines for women, since it is full of references to personal hygiene. The letter initially elides Buffet’s request to use the name Dada and goes on to define the movement in a typically unclear manner. This ambivalent document was part of Tzara's attempt to regain control of Dada, since he used it to advertise Dadaglobal, a luxurious volume that was never published. It is likely that Tzara saw New York Dada as a vehicle to reposition himself as the head of the movement or at the very least, to ally himself with Dadaists outside of Europe. This would prove a prescient, if useless move, since after leaving New York for Paris, Francis Picabia abandoned Dada in May 1921, foreshadowing his and Breton’s attacks against Tzara in 1922 as well as the movement’s demise.

Hage has rightly noticed that New York Dada subverted and reinforced gender roles and consumerism, and Tzara's letter is likewise contradictory. He begins by noting that Dada belongs to all, much like God and toothbrushes, and references to hygiene and beauty rituals appear throughout his letter. He also mentions that although Dada was not a dogma, a school, or a “glossy label,” it functioned as an “anti-nuance cream” against logic and conventions. Moreover, the letter suggests an awareness regarding the increasing globalization of fashion, beauty standards, products, magazines, and artistic movements, tropes which he leveraged to advertise his book, Globaldada. Tzara ends the letter by restating that Dada was a not only remedy, but also a luxury as well as a necessity that could aid the heart, intelligence, and wrinkles.

New York Dada, page 4 with photographs of Elsa Hildegard Baroness von Freytag-Loringhoven and a poem attributed to her, “YOURS WITH DEVOTION trumpets and drums.” Monoskop.

New York Dada, page 2 with photomontage by Man Ray and letter from Tristan Tzara. Monoskop.

According to Tzara’s letter, Dadaglobe would include works from artists based in Berlin, Cologne, Hannover, New York, Paris, and Zürich, places which have typically been associated with this movement. He also mentions individuals from other latitudes, likely to assert his own leadership at the helm of an increasingly amorphous movement: Amsterdam, Brussels, Calcutta, Chile, Leyden, Madrid, Mantua, Rome, Moscow, Münich, and Prague. This list expanded the cosmopolitan nature of his magazine Dada, which featured artists from several European countries, and authorized, in a sense, Duchamp and Man Ray's codification of its American variant. Ironically, it appears that New York Dada more or less closed with this city’s Dada season, a contradiction fully in line with Duchamp’s approach to art and its conventions.

In many ways, New York Dada and Tzara's participation within it seemed to recognize the need to seek kindred spirits outside of Germany, France, and Switzerland, as Tzara himself confirmed by stressing Dadaglobal's reach. Moreover, both the magazine and the letter point to the fact that New York was rising as an important modernist center well before it “stole” modern art from Paris after the consolidation of Abstract Expressionism. Although World War II secured the importance of this city as an artistic center, the years surrounding the Great War anticipated this process due to the migration of important figures such as Francis Picabia, Duchamp, and Dreier, a cosmopolitan jolt that was reinforced by individuals from Latin America, such as Marius de Zayas [about whom see Aguirre’s April 5, 1920 guest-post] , José Juan Tablada, Miguel Covarrubias, and Joaquín Torres García; plus many other notable international arrivals, such as P.G. Wodehouse, John Butler Yeats, Anna Pavlova, and Yasuo Kuniyoshi. New York’s cultural scene was also shaped by the Harlem Renaissance, fueled by southern Black arrivals; like Dada and other avant-garde movements, it had important transatlantic implications. Thus, whereas New York Dada certainly exploited the tension between gender roles and their ironic reconfiguration, it also linked the New York group and Tzara's use of Dadaglobal to envision a worldwide movement. In retrospect, it appears that Man Ray and Duchamp published the issue of New York Dada in order to put an end to this season, and this droll magazine illustrates how they reconfigured Tzara’s nonsensical movement by incorporating American mass culture. At the same time, the magazine prolonged Tzara and other European Dadaists’ tirade against nationalism, further demonstrating this anti-dogma’s appeal to individuals on both sides of the Atlantic and beyond.

References/Further Reading

Hage, Emily. “The Magazine as Readymade: New York Dada and the Transgression of Genre and Gender Boundaries.” The Journal of Modern Periodical Studies 3, no. 2 (2012): 175-197.

Hopkins, David. “New York Dada: From End to Beginning,” in A Companion to Dada and Surrealism, edited by Hopkins, 70-88. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons Inc., 2016.

– Mariana Aguirre, April 12, 2021.

Mariana Aguirre is an art historian specializing in Italian Modernism and modernist primitivism. She is currently a Research Professor at the Instituto De Investigaciones Estéticas (UNAM), In Mexico City.

TAGS: visual art, avant-garde, modernism, little magazines, gender, women, fashion magazines, consumerism, expatriates