James Weldon Johnson’s “Self-Determining Haiti”

TODAY'S GUEST POST IS BY RAPHAEL DALLEO, BUCKNELL UNIVERSITY (SEE FULL BIO BELOW)

One hundred years ago today..., James Weldon Johnson published the first in a series of four articles in the Nation about the U.S. occupation of Haiti. Under the title “Self-Determining Haiti,” Johnson’s articles would support a massive backlash against the occupation, especially among New York’s Black community. While Johnson’s expose and other activism against the occupation led to Senate hearings and even influenced the presidential election that year, US Marines would remain in Haiti until 1934.

[Editor: Johnson has been a pivotal figure for NY1920. See a list of previous posts about him here.]

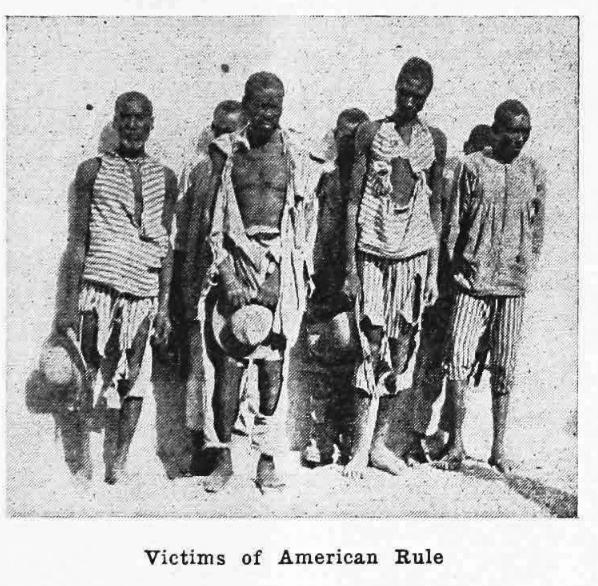

“To know the reasons for the present political situation in Haiti, to understand why the United States landed and has for five years maintained military forces in that country, why some three thousand Haitian men, women, and children have been shot down by American rifles and machine guns, it is necessary, among other things, to know that the National City Bank of New York is very much interested in Haiti,” Johnson’s article begins. From there, he details how National City Bank (today’s Citigroup) pressured the U.S. to send military forces to Haiti in 1915, took control of the country’s finances, and diverted Haiti’s revenue away from education or infrastructure and towards enriching U.S. investors.

The Crisis, September 1920, p. 217. Modernist Journals Project.

The Crisis, September 1920, p. 223. Modernist Journals Project.

Johnson’s series, along with an article he published in the NAACP’s The Crisis in September 1920, burn with indignation at the bald-faced plunder of the hemisphere’s only independent Black nation at the time, carried out by a Wall Street firm supported by U.S. military might. Democratic vice presidential candidate Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who had overseen the occupation as assistant secretary of the Navy and even bragged about writing Haiti’s constitution himself, was put on the defensive by the bad press during a campaign that would eventually see Republican Warren Harding elected president.

The Messenger, October 1920, p. 100. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library.

Johnson’s reporting on the occupation circulated widely among Black New Yorkers. Socialist activist Hubert Harrison, who had immigrated to New York from St. Croix, published a series of articles in the Universal Negro Improvement Association’s Negro World that reference Johnson’s investigative journalism in calling attention to “the bloody rape of the republics of Haiti and Santo Domingo.” The October 1920 issue of The Messenger, whose editors at the time included the Jamaica-born W.A. Domingo, begins with a simple announcement: “From all accounts, it seems that the National City Bank of New York is the government of Haiti.”

Cyril V Briggs, and Robert A Hill, The Crusader. New York ; London : Garland, 1987.

The African Blood Brotherhood (ABB) became especially vocal critics of the occupation. This group of mostly Caribbean-born New Yorkers had published articles about Haiti in their mouthpiece, The Crusader, focused on the occupation as a violation of Haiti’s sovereignty and a sign of Woodrow Wilson’s hypocrisy. Articles from March and May of 1920 by the Nevis-born editor, Cyril Briggs, describe how “American marines, at Mr. Wilson’s behest, engaged in scrapping the Haitian and Dominican Constitutions” and how the president justifies military force as “undertaken in the interests of ‘law and order’ and ‘humanity’.” By the fall of 1920, the articles in The Crusader were mounting a new attack; in October 1920, Briggs published his longest article on Haiti, quoting extensively from Johnson’s reporting to foreground economic exploitation on the island. It is surely no coincidence that by the end of 1920, the African Blood Brotherhood had become aligned with the US Communist party (and become the first Black communists in the US).

Analyzing the occupation, and in particular the role of US finance capitalism in engineering the intervention, forced this radical group of Caribbean New Yorkers to question political independence as the goal of anticolonialism and see international communism as an ideology better able to critique and combat the economic domination at the heart of imperialism. The activism of Harrison, Domingo and Briggs against the occupation would continue throughout the 1920s, giving them an important issue to rally African Americans against US imperialism and to show white leftists in the US the intersection of economic exploitation and race.

Further reading:

For more on responses to the occupation, see Raphael Dalleo, American Imperialism’s Undead: The Occupation of Haiti and the Rise of Caribbean Anticolonialism (University of Virginia Press, 2016).

See also Suzy Castor, L’occupation américaine d’Haïti (Imprimerie Henri Deschamps, 1988); Peter Hudson, Bankers and Empire: How Wall Street Colonized the Caribbean (University of Chicago Press, 2018); Mary Renda, Taking Haiti: Military Occupation and the Culture of U.S. Imperialism (University of North Carolina Press, 2001); Hans Schmidt, The United States Occupation of Haiti, 1915-1934 (Rutgers University Press, 1995).

WRITTEN BY RAPHAEL DALLEO. AUGUST 28, 2020.

RAPHAEL DALLEO IS PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH AT BUCKNELL UNIVERSITY. HIS BOOK AMERICAN IMPERIALISM’S UNDEAD: THE OCCUPATION OF HAITI AND THE RISE OF CARIBBEAN ANTICOLONIALISM (UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA PRESS, 2016), WON THE 2017 CARIBBEAN STUDIES ASSOCIATION AWARD FOR BEST BOOK ABOUT THE CARIBBEAN. HE IS COEDITOR WITH CURDELLA FORBES OF THE FORTHCOMING CARIBBEAN LITERATURE IN TRANSITION, 1920-1970 (CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS, 2021).

TAGS: Haiti, occupation, US imperialism, African American communism, Harlem Renaissance, race, economics